Unwitting snake oil?

The Market for Silver Bullets

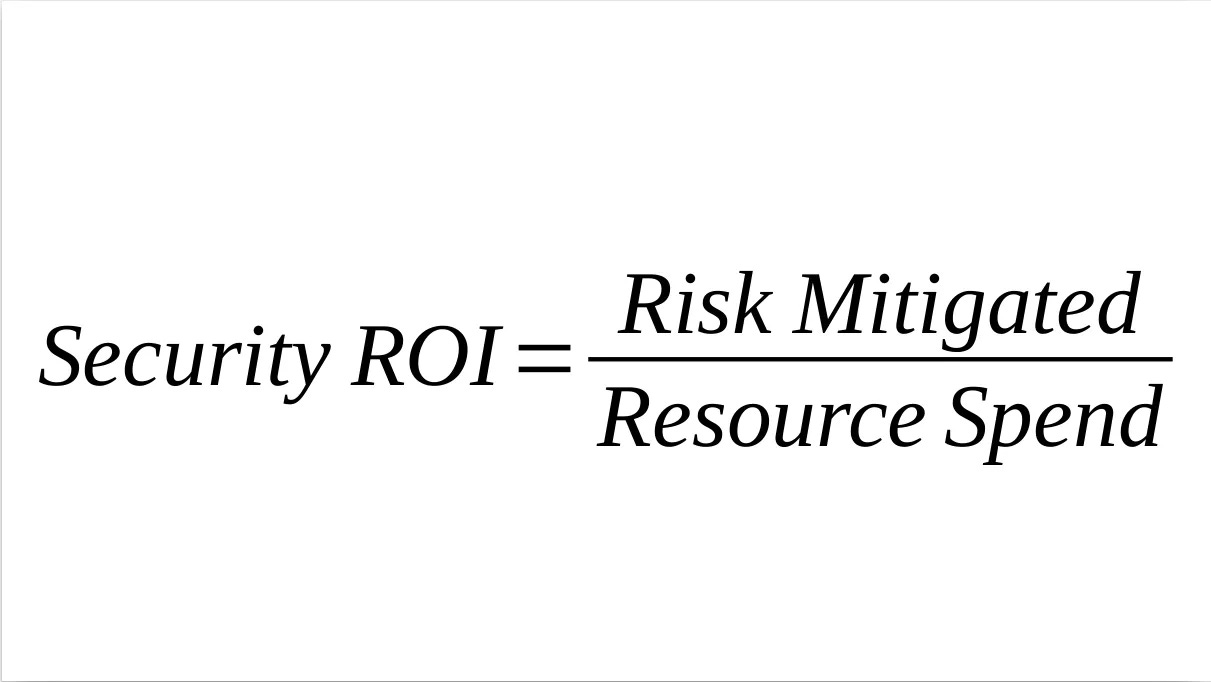

I spend a lot of time thinking about how to spend company resources of money and time as a CISO. I’d even go so far as to say that crafting efficient spend to maximize risk mitigated for the lowest price point is the CISO’s core job function.

So I was delighted to discover this 2008 research paper called “The Market for Silver Bullets” (H/T Ross Haleliuk).

Very little has changed since Ian Grigg wrote this paper almost twenty years ago. There are so many quotable quotes in this paper I feel like a preacher man underlining the entire Bible while writing a sermon. To wit:

“1. Good enough is good enough. 2. Good enough always beats perfect. 3. The really hard part is determining what is good enough. […] We are completely clueless about what is good enough. That is the rub. Business people cannot tell us because they don’t understand security, and security people cannot tell us because they don’t understand business.” [emphasis mine]

This is the fundamental service that a CISO contributes—I bridge the divide between business and security.

This is why a business person without technical chops cannot succeed as a CISO, and it's likewise why so many deeply-technical security engineers fail as a CISO. You have to be a bridge between the two worlds.

I've written about this many times before.

Which leads us back onto the well-worn groove of negotiating with security vendors. How much is a security vendor worth to your employer, anyway?

Quantitative metrics are worthless when planning strategic security investment, as I’ve frequently (and apparently controversially) written about as well. There are no metrics capable of answering the question “Is this money well spent or not.” Risk management is a handwavy art and that is not likely to change anytime soon, no matter what the prevailing dogma would have you believe.

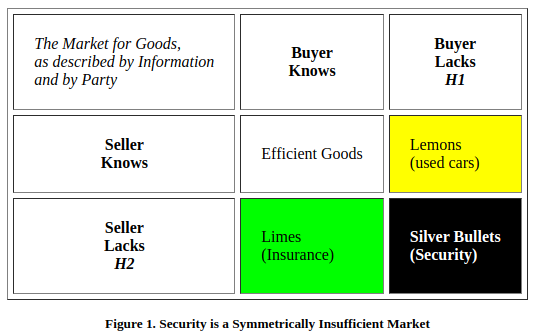

Why is that? Griggs lays it out beautifully:

Neither buyers nor sellers have sufficient information to make rational decisions when trading in cybersecurity services. The whole thing is a bit of a sham. While some vendors are premeditated snake oil, those are usually easy to spot, so we are concerned here with legit, non-snake oil vendors, of which there are many who operate and sell in good faith.

Good faith buyer (CISO, e.g. me) meets good faith seller (security vendor).

Neither of us has any real way to know the true financial value to each other of the transaction we are discussing.

Therefore the rational position for a buyer (a CISO) to take is to engage in negotiation as a form of price discovery. If you don’t know how much something is worth, but you still want to buy it, then you should pay as little as possible for it.

Likewise a rational vendor would take the opposite approach: If you don’t know how much something is worth, but you still want to sell it, then you should charge as much as possible for it as you can.

This approach is especially true with new vendors, because as Griggs points out it’s a bit of a lottery—if you sign a multi-million dollar contract and the vendor turns out to be rubbish, that’s a bad deal for your employer (but a great deal for the vendor).

The central question of strategic security leadership is all about the ROI. That makes money a central question for the CISO.

I often notice, to my chagrin, that because I spend so much time thinking about money and Security ROI, I don't have time to spend dozens of hours a week going down the technical rabbit holes like I used to, and I admit I sometimes feel inferior to my direct reports when they come up with a specific detail that shows they are a head length ahead of me in a particular technical dimension.

But then I realize that what I do is also a deep specialization that I spend dozens of hours of week working on: Money, time, risk, and Security ROI.

That's the true test of CISO: Maximizing Security ROI.

I wrote this a year ago now, and it remains my north star: