Make Sure We Never Get Hacked

How not to measure a CISO's job performance

An innocent approach to measuring the performance of the security job function would be to measure the number or magnitude of security incidents. But the closer you look at the problem space, the more it becomes clear this does not make sense.

Security risk is business risk, and the decision to accept risk or do something about that risk is a business decision. Business decisions that involve trade-offs of accepting risk or authorizing budgetary spend are decisions for the CEO and Board of Directors.

The SEC codifies this sensible logic in new regulatory guidance for listed companies.

Why does this make sense? And what is a CISO responsible for anyway, if not to “build a wall to keep the hackers out”?

Well, first of all you could spend all the money in the known universe and never get to perfect security. In fact, we aren’t trying to reach perfection. We’re trying to live in the real world and make pragmatic decisions that are good for business.

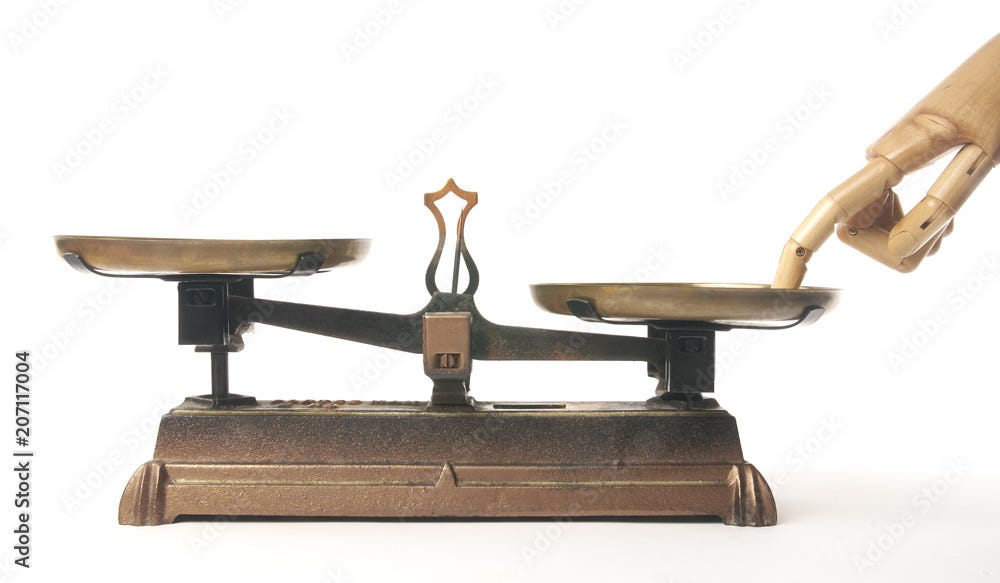

That means there is always a sliding scale between risk acceptance and security budget.

Your CISO is responsible, and should be held responsible, for identifying risk, for making good recommendations for managing risk, and then executing to meet the risk tolerance of the business within the given budget of time and money.

Let's take a couple of hypothetical case study scenarios to walk through the nuance here.

1) Let’s say your CISO flags a specific risk to you, and as management, you accept the risk and choose not to do anything about it. That risk then materializes and causes your business financial harm. Is the CISO at fault? Clearly no, because they did their job and warned you of the risk. You chose to accept the risk.

2) Let’s take a case study where your CISO has limited organizational authority. There can be no responsibility without authority. As human beings and as employees we are responsible for the things we can control. We are not responsible for the things we cannot control. This is a pretty basic observation but very important. Your CISO does not have budgetary authority to spend unlimited amounts of money and time. (Nor should they.) Your CISO, depending on the company, may have little or no governance authority to enforce preventive security measures. Do you fairly measure the job performance of someone by what is outside of their power to deliver? If you do not give a CISO authority to prevent security incidents, then you can hardly hold them responsible when security incidents materialize.

3) Let’s give the CISO no budget, no authority, and keep them as a “Scapegoat-in-Waiting” to throw to the wolves as a PR stunt when something bad happens. If you think that’s a joke, think again. Over the last quarter century this has happened over and over again. This might make yourself feel better, but it doesn’t do anything to manage the risk of a security incident impacting your business negatively.

Part of a CISO’s job is to educate their Board of Directors and executive leadership so they understand how to manage security risk. This also is a vital part of the job.

But using “did we get hacked or not” as a measure of a CISO’s job performance? That would be like judging your General Counsel on “did we get sued or not”.

That’s no way to run a business.